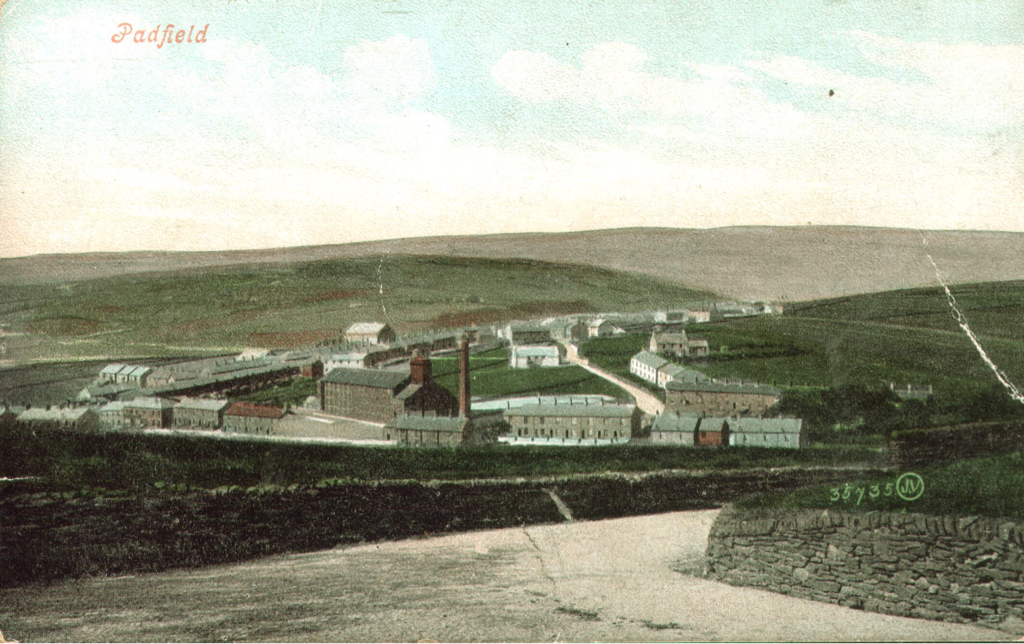

Above photo: Postcard of Rhodes' Mill complex, the millpond and Platt Street.

A brief history of Padfield

Written by Steve Gwilt

Padfield is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 and has a long and varied history. It was originally known as Padefeld, possibly from the Padda (a name) or from Padde (meaning toad) and feld (meaning plain, pasture, open or cultivated land). The writers of the Domesday Book weren't impressed though, "All Longdendale is waste," they wrote, although this may have been because King William's army had wasted it during the harrying of the north in 1069-70.

The Normans administered the whole area as a Royal Forest, and this continued until 1290 when most of the forest rules were lifted by King Edward I. The ownership of the land was passed from royal to royal, eventually being granted to the Abbot of Basingwerke at the end of the 1100s. The Abbot as Lord of the Manor owned four-fifths of the land, and by the end of 15th century this had all been leased to the Talbots (the Earls of Shrewsbury), who became outright owners after the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. When the Talbot line eventually died out, the ownership passed by marriage to Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel. The Howards remained as Lords of the Manor until 1926.

Three or four hundred years ago, Padfield was a very different place to what we see today. The village was a stopping place on the salt route from the salt ‘wyches’ of Cheshire to the iron foundries that grew up around the Sheffield area. Padfield was a small community which for generations had earned its living from farming, and its associated crafts and trades. Some small-scale weaving took place in the homes to produce clothes for the farmers and their workforce.

Padfield is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 and has a long and varied history. It was originally known as Padefeld, possibly from the Padda (a name) or from Padde (meaning toad) and feld (meaning plain, pasture, open or cultivated land). The writers of the Domesday Book weren't impressed though, "All Longdendale is waste," they wrote, although this may have been because King William's army had wasted it during the harrying of the north in 1069-70.

The Normans administered the whole area as a Royal Forest, and this continued until 1290 when most of the forest rules were lifted by King Edward I. The ownership of the land was passed from royal to royal, eventually being granted to the Abbot of Basingwerke at the end of the 1100s. The Abbot as Lord of the Manor owned four-fifths of the land, and by the end of 15th century this had all been leased to the Talbots (the Earls of Shrewsbury), who became outright owners after the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. When the Talbot line eventually died out, the ownership passed by marriage to Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel. The Howards remained as Lords of the Manor until 1926.

Three or four hundred years ago, Padfield was a very different place to what we see today. The village was a stopping place on the salt route from the salt ‘wyches’ of Cheshire to the iron foundries that grew up around the Sheffield area. Padfield was a small community which for generations had earned its living from farming, and its associated crafts and trades. Some small-scale weaving took place in the homes to produce clothes for the farmers and their workforce.

By the early 17th century some local people saw weaving and the woollen industry as their main employment. Padfield was the largest Hamlet in the area. It had some of the largest farms, and some of the farmers were quite wealthy. For example, John Dearnelye of Padfield, yeoman, had 26 books in 1706 – quite remarkable for that time.

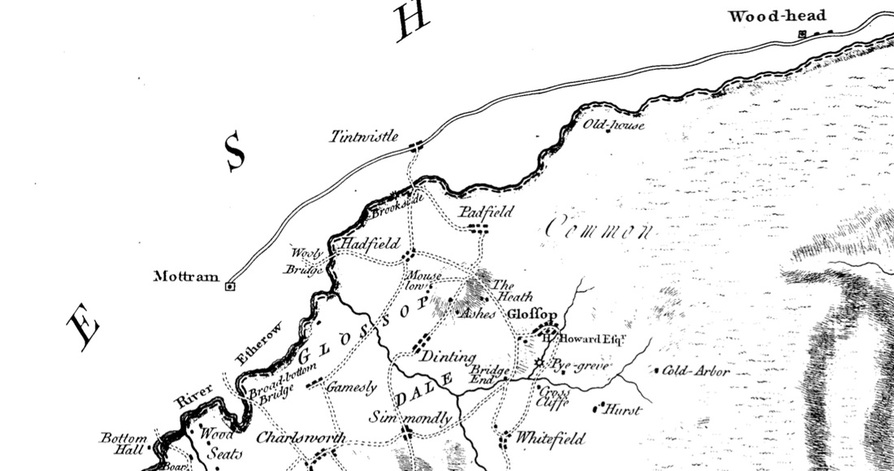

So life carried on in much the same way; but all this was soon to change. The mid-1700s saw the first textile mills appearing in the area. The water mill a Waterside on the Etherow, was probably the first, and is clearly shown on a map of 1767. By 1795 maps show the site had three more buildings on it and the site was labeled “Turners Factory." The turn of the century saw a massive expansion of the cotton industry in Glossopdale. In Padfield village, the first real industrial development was started by Robert Lees, who built Padfield Brook Mill in 1793. The mill was to the rear of Padfield Brook House, and by 1841 Lees was employing 103 people there.

On Platt Street in the early 1800s there were no fewer than three separate mills. These were all eventually pulled down to make way for Rhodes’ Hadfield Mill complex, also known as Hadfield Mill or Rhodes Top Mill, in about 1874. The remnants of this mill are still visible on Platt Street. At the bottom of Platt Street was a further mill, Station Mill, built by Thomas Platt in 1862. This mill eventually became known as Willman’s Mill. Where modern-day Padfield meets Tintwistle and Hadfield was the mighty Waterside Mill complex. This was the biggest firm in the area and when Bridge Mill was completed in 1854, this group of mills was possibly the largest single industrial unit in the world! Waterside Mills employed up to ten times as many people as the other Padfield mills put together.

So life carried on in much the same way; but all this was soon to change. The mid-1700s saw the first textile mills appearing in the area. The water mill a Waterside on the Etherow, was probably the first, and is clearly shown on a map of 1767. By 1795 maps show the site had three more buildings on it and the site was labeled “Turners Factory." The turn of the century saw a massive expansion of the cotton industry in Glossopdale. In Padfield village, the first real industrial development was started by Robert Lees, who built Padfield Brook Mill in 1793. The mill was to the rear of Padfield Brook House, and by 1841 Lees was employing 103 people there.

On Platt Street in the early 1800s there were no fewer than three separate mills. These were all eventually pulled down to make way for Rhodes’ Hadfield Mill complex, also known as Hadfield Mill or Rhodes Top Mill, in about 1874. The remnants of this mill are still visible on Platt Street. At the bottom of Platt Street was a further mill, Station Mill, built by Thomas Platt in 1862. This mill eventually became known as Willman’s Mill. Where modern-day Padfield meets Tintwistle and Hadfield was the mighty Waterside Mill complex. This was the biggest firm in the area and when Bridge Mill was completed in 1854, this group of mills was possibly the largest single industrial unit in the world! Waterside Mills employed up to ten times as many people as the other Padfield mills put together.

It is difficult to imagine the dramatic changes that Padfield must have seen. Four times as many people in just 40 years, brought in mainly from Yorkshire, to feed the ever-increasing demand for a workforce to process cotton. In 1841 more than half the population was born outside the county, as the demand for cotton workers outstripped the local supply.

1838 saw the start of work on the Woodhead railway tunnel. The poor working conditions in which the navvies worked were notorious. 32 men were killed, and over 240 serious injuries were recorded in creating the longest railway tunnel in Britain at the time – over three miles long. At one point over 1,500 men were employed on the project. The Sheffield, Ashton under Lyne and Manchester Railway eventually opened in 1845. Then in 1847 another tunnel was begun which finally opened in 1852.

In 1848 work started on the construction of the Woodhead Reservoir. Hundreds of workers moved into the area, and a whole shanty town, New Yarmouth, was created in Rhodes Wood to house the workers and their families. Diabolical living conditions, overcrowding and poor sanitation were the order of the day – as was drunkenness. A Padfield farm-hand born at the start of the 1800s must have been amazed at the transformation of the local area.

1838 saw the start of work on the Woodhead railway tunnel. The poor working conditions in which the navvies worked were notorious. 32 men were killed, and over 240 serious injuries were recorded in creating the longest railway tunnel in Britain at the time – over three miles long. At one point over 1,500 men were employed on the project. The Sheffield, Ashton under Lyne and Manchester Railway eventually opened in 1845. Then in 1847 another tunnel was begun which finally opened in 1852.

In 1848 work started on the construction of the Woodhead Reservoir. Hundreds of workers moved into the area, and a whole shanty town, New Yarmouth, was created in Rhodes Wood to house the workers and their families. Diabolical living conditions, overcrowding and poor sanitation were the order of the day – as was drunkenness. A Padfield farm-hand born at the start of the 1800s must have been amazed at the transformation of the local area.

The railway eased the flow of raw materials into the mills and finished goods out of them. Consequently, the mill owners soon became powerful men. Like the farmers before them, they played an important role in the governance of the area.

The wealth and power of the great mill owners was built on the toil of ordinary Padfield folk and life for the working classes would, by today's standards, have been unbelievably harsh. In 1842 a Government Commission found examples of children aged four working in mines, where the normal starting age of work was between eight and nine years old. The textile mill system also employed young children, who could more easily manoeuvre between the looms because of their small size. Health and safety were words that meant nothing, and many children suffered serious injury for their meagre rewards. Indeed it was not until 1870 that education was made legally compulsory for children up to the age of 10. However, compulsory attendance for 5-10 year olds was not the law until 1880. Fortunately, it seems that the local mill owners were probably better than elsewhere in the country at treating their workforce compassionately. Nevertheless, a glance of the memorials in Glossop Cemetery gives an indication of the misery and distress ordinary families had to face.

The cotton industry faced its first major test during the 1860s when the cotton famine, brought about by the blockade of cotton supplies during the American Civil War, caused misery to the area. No cotton meant no work. Hundreds of families left the area to try to find employment. From 2,051 residents in 1851, Padfield’s population dropped to 1,619 in 1861 and was still only 1,699 ten years later.

The wealth and power of the great mill owners was built on the toil of ordinary Padfield folk and life for the working classes would, by today's standards, have been unbelievably harsh. In 1842 a Government Commission found examples of children aged four working in mines, where the normal starting age of work was between eight and nine years old. The textile mill system also employed young children, who could more easily manoeuvre between the looms because of their small size. Health and safety were words that meant nothing, and many children suffered serious injury for their meagre rewards. Indeed it was not until 1870 that education was made legally compulsory for children up to the age of 10. However, compulsory attendance for 5-10 year olds was not the law until 1880. Fortunately, it seems that the local mill owners were probably better than elsewhere in the country at treating their workforce compassionately. Nevertheless, a glance of the memorials in Glossop Cemetery gives an indication of the misery and distress ordinary families had to face.

The cotton industry faced its first major test during the 1860s when the cotton famine, brought about by the blockade of cotton supplies during the American Civil War, caused misery to the area. No cotton meant no work. Hundreds of families left the area to try to find employment. From 2,051 residents in 1851, Padfield’s population dropped to 1,619 in 1861 and was still only 1,699 ten years later.

The prosperity of Glossopdale returned for the next twenty years, owing to larger mills, more spindles and more efficiency. By 1891 Padfield had 2,573 inhabitants and 557 houses. 1887 marked Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, and this was widely celebrated by all. Padfield was a thriving community. Kelly’s Derbyshire Directory of the Jubilee year lists 21 shops in Padfield. They included two butcher's shops, a baker's shop, two fishmongeries, two grocery shops, two draper's and tailor's shops, a newsagent, a confectioner, an insurance agent, a clogger, and of course the Co-op. By 1901, commercial activity seems to have hardly changed with many of the same trades and businesses still in place - see Padfield Occupations from the 1901 census along with definitions.

As well as the shops, there were the inns and alehouses. The Peels Arms we see today has been licensed since at least 1845, and there have been many other alehouses and clubs in the village and its vicinity. Alongside the commercial activities, there was of course a spiritual side to life. The early Wesleyan Chapel and Sunday School on Padfield Main Road was superseded in 1880 by the present building on Post Street. The new chapel was able to seat 400 worshippers. On Temple Street the Padfield Independent Chapel was built in 1829 and extended in 1901.

As well as the shops, there were the inns and alehouses. The Peels Arms we see today has been licensed since at least 1845, and there have been many other alehouses and clubs in the village and its vicinity. Alongside the commercial activities, there was of course a spiritual side to life. The early Wesleyan Chapel and Sunday School on Padfield Main Road was superseded in 1880 by the present building on Post Street. The new chapel was able to seat 400 worshippers. On Temple Street the Padfield Independent Chapel was built in 1829 and extended in 1901.

The 1890s saw the start of a downturn in trade in the area generally. The 1914–1918 war heaped further misery on the area. The Hadfield War Memorial commemorates 160 men from Hadfield and Padfield who lost their lives in the war. How many of these men were from Padfield is difficult to say, but there is a plaque in the Temple Street Chapel listing 13 men who were associated with its Sunday School. The post war downturn in manufacturing, the consequences of deflation, the pay cuts and slump of the 1920s, and the mass unemployment of the 1930s, all took their toll. In the mid-1930s Glossop had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country.

There was a brief pick up in trade during the 1939–1945 World War, but again at the cost of the lives of local people. The Hadfield War Memorial lists the names of 38 men and one woman who gave their lives, and there is a simple plaque in the Temple Street Chapel commemorating James Eastwood, Sam Lawton, Matthew H Pearson, Stanley Russell and Albert Scarratt.

Yet it seems Padfield was still thriving. A 1941 Directory lists 12 shops dotted around the village. The Co-op was still going strong at 99 Platt Street, and there were shops selling confectionery, hardware and groceries, as well as both a general store and a tripe dresser. Sadly, the slide in manufacturing continued. Mills continued to close and areas of Padfield became very run down. By the late-1950s the area’s mills had virtually disappeared. In 1976 Waterside Mills complex finally closed, after more than 200 years of continuous activity.

As the mills closed down, so did the shops. Just one mill building still stands in Padfield in the 21st Century - Rhodes Mill on Platt Street - now with just two floors and a diminished ground floor area. The shops and most of the pubs were converted into houses. Only the Peels Arms remains as a viable commercial property. One of the chapels - the Wesleyan Chapel on Post Street - was converted into apartments and so we arrive at the Padfield we see today.

We have compiled a small collection of images in our Padfield's Past Gallery; photographic images of Padfield from its industrial past to more recent times when the cotton industry was in decline. Step back in time and see the mills as they were, the shopkeepers, the streets and a few snow drifts the height of a house!

There was a brief pick up in trade during the 1939–1945 World War, but again at the cost of the lives of local people. The Hadfield War Memorial lists the names of 38 men and one woman who gave their lives, and there is a simple plaque in the Temple Street Chapel commemorating James Eastwood, Sam Lawton, Matthew H Pearson, Stanley Russell and Albert Scarratt.

Yet it seems Padfield was still thriving. A 1941 Directory lists 12 shops dotted around the village. The Co-op was still going strong at 99 Platt Street, and there were shops selling confectionery, hardware and groceries, as well as both a general store and a tripe dresser. Sadly, the slide in manufacturing continued. Mills continued to close and areas of Padfield became very run down. By the late-1950s the area’s mills had virtually disappeared. In 1976 Waterside Mills complex finally closed, after more than 200 years of continuous activity.

As the mills closed down, so did the shops. Just one mill building still stands in Padfield in the 21st Century - Rhodes Mill on Platt Street - now with just two floors and a diminished ground floor area. The shops and most of the pubs were converted into houses. Only the Peels Arms remains as a viable commercial property. One of the chapels - the Wesleyan Chapel on Post Street - was converted into apartments and so we arrive at the Padfield we see today.

We have compiled a small collection of images in our Padfield's Past Gallery; photographic images of Padfield from its industrial past to more recent times when the cotton industry was in decline. Step back in time and see the mills as they were, the shopkeepers, the streets and a few snow drifts the height of a house!

A Portrait of Padfield (book)

|

As part of the Millennium celebrations, the Padfield Residents’ Society decided to produce a visual history of Padfield. A large number of residents, and former residents, were asked to contribute photographs of the village, its people and activities over the years. Although this had taken longer than originally envisaged, the brief history you have just read forms only a small portion, an introduction so to speak, of the well-researched and informative publication that was compiled and edited by Janis Birchall on behalf of the Padfield Residents' Society. The book, however, was a collaboration of many people's labours.

Going beyond the national occasions, the world events and the lives of the rich and famous, instead, A Portrait of Padfield captures the essence of the village, revealing a record for the future of the lives of ordinary Padfielders and what they got up to during a period of time photography has been available to us. From the writer: "There are, of course, many gaps in our record. People suffering grinding poverty have better things to do with their lives than take photographs! We have managed to turn up very little indeed from the early parts of the twentieth century. But we do think that these “Snapshots of Padfield” are a valuable historical record. We hope it will inspire you to think about those who went before us, spark some memories and, more importantly, help cement us even more firmly together as a vibrant village community." |